Pop Up #4: Night at the Art Gallery

as told by Yu-Chi (Jacky) Cheng

(with photos by Yoshihito Saito, Emily Zhang, Michael Chen, and myself)

Visions – MINCE’s and mine

What is cooking, to you, to me, and to MINCE? I used to believe that cooking was about nourishment, about expressing affection through food, about caring for my loved ones. Yet in this unforgiving world of psets and exams that is MIT, who truly has the time to sit down and enjoy a multi-course meal? In the age of fast food and even faster food delivery, who has the patience to indulge themselves with a home-cooked dish? Before MINCE, I plodded through my culinary Odyssey alone, developing an increasingly bizarre palate, chewing through all sorts of organ meats, exotic fauna, and outlandish taste profiles that could be best described as “acquired tastes.” After indulging the most twisted, peculiar desires of my palate with one unorthodox creation after another, I found myself wondering if my new, highly personal style of cooking could still connect with those around me. Can cooking truly be an act of love, if the only person I’m nourishing is myself?

Seeking an answer to my question, I joined MINCE. Cooking for MINCE was far more challenging than doing it for family and friends, or for myself. I had no idea about the preferences of the guests: what flavors they would like; what foods would be closest to their hearts; what memories each dish would bring to their minds. It was like screaming into a void and never hearing any echo back from the abyss. Over the course of three events, I tried to convince myself that I could live up to MINCE’s mission of creating genuine human connection through food. I tried to prove to myself that I was indeed capable of sharing love. I tried to reconcile my own philosophy of cooking as an expression of affection, with MINCE’s goal of sharing this affection with the community. Each pop-up, to me, was like baring my heart in front of a public audience, like a confession sung out into empty space, filled with the vulnerability of not knowing how the guests would respond to my cooking.

So when Angela asked me what vision I had for this pop-up, I thought long and hard about what I could offer to the guests, and to MINCE. What part of me would a generic, American audience love? What part of my culinary philosophy could give my friends in MINCE a memorable experience? In the end, I decided to follow the great American chefs who inspired me to believe in “cooking as nourishment” in the first place, and settled on the theme of “modernist cuisine.”

“Modernist cuisine” was easy to say but hard to define. Of course, we could claim that any innovation we make in the cooking process is inherently modernist, but would that message resonate with our guests? In an attempt to guide the pop-up in some tangible direction, I pieced together a few hallmarks of what modernist cuisine meant to me, to serve as guidelines during menu ideation. Among those hallmarks were: sous vide cooking, transformation of ingredients, the use of special ingredients, the incorporation of foams, and the concept of the “multisensory experience.” Luckily, these ideas resonated with MINCE. Looking back at my original vision, I am now amazed by how thoroughly the MINCE team realized this dream of mine – this far-flung moonshot that I never could have accomplished without this wonderful group of friends who all shared with me the same love for food.

The birth of the MINCE portable kitchen

A major challenge in this pop-up was to prepare and serve food in the Long Lounge (7-429) – an on-campus venue with no easily accessible kitchens nearby. For past pop-ups, we always chose spaces that were adjacent to kitchen facilities. This time, however, we wanted to try moving away from that constraint. If this worked, we thought, it would pave the way for MINCE to serve food at any location, in true pop-up fashion.

Luckily for us, there was an unoccupied empty space, ahem, I mean, open-concept floor plan kitchen, ready for move in. We used wooden staging blocks as workstations, and arranged them so that the preparations for each dish would not interfere with each other – starter and drink on one side, main and dessert on the other.

In front of the cooking stations were a set of long tables that, in my opinion, formed the beating heart of the MINCE portable kitchen: the pass. The pass was where dishes from the cooking stations were plated and passed to the service staff; and finished plates from the dining room were passed back into the kitchen. It was where the cook and business teams interfaced with each other, where all the impromptu decisions about pacing, personnel scheduling, and last-minute logistics were made. It was where every person in MINCE got to interact with every other person. It was a magical place where, for a few precious hours, I viscerally felt the whole team move toward a common goal. If cooking was indeed an expression of love, the pass of the MINCE portable kitchen was definitely the most loving place on campus during those moments.

Leaving the comfort zone of a regular kitchen meant that we had to design our menu accordingly. Any dish that required a stove was out of the question. Fortunately, modernist cuisine offered a solution: sous videcooking. This method of vacuum-sealing food and gently cooking them in constant-temperature water baths not only yielded exceptional texture and taste, it also allowed us to cook wherever electricity was available. With three sous vide machines, a toaster oven, and an airfryer that we managed to scrounge up, we managed to gather enough heating power to cook our main course in time, on site.

The rest of the menu we served cold. Well, mostly cold. There was one exception – an exception that involved a portable yet flamboyant method of heating that has carved its status in MINCE’s short history as an essential kitchen tool – the blowtorch. First employed by Joanna and myself in the New England pop-up as a kitchen gadget like any other, the blowtorch was elevated at Michael’s suggestion into a component of tableside service.

Starter – “Birth of Venus” Boticelli’s scallop nigiri

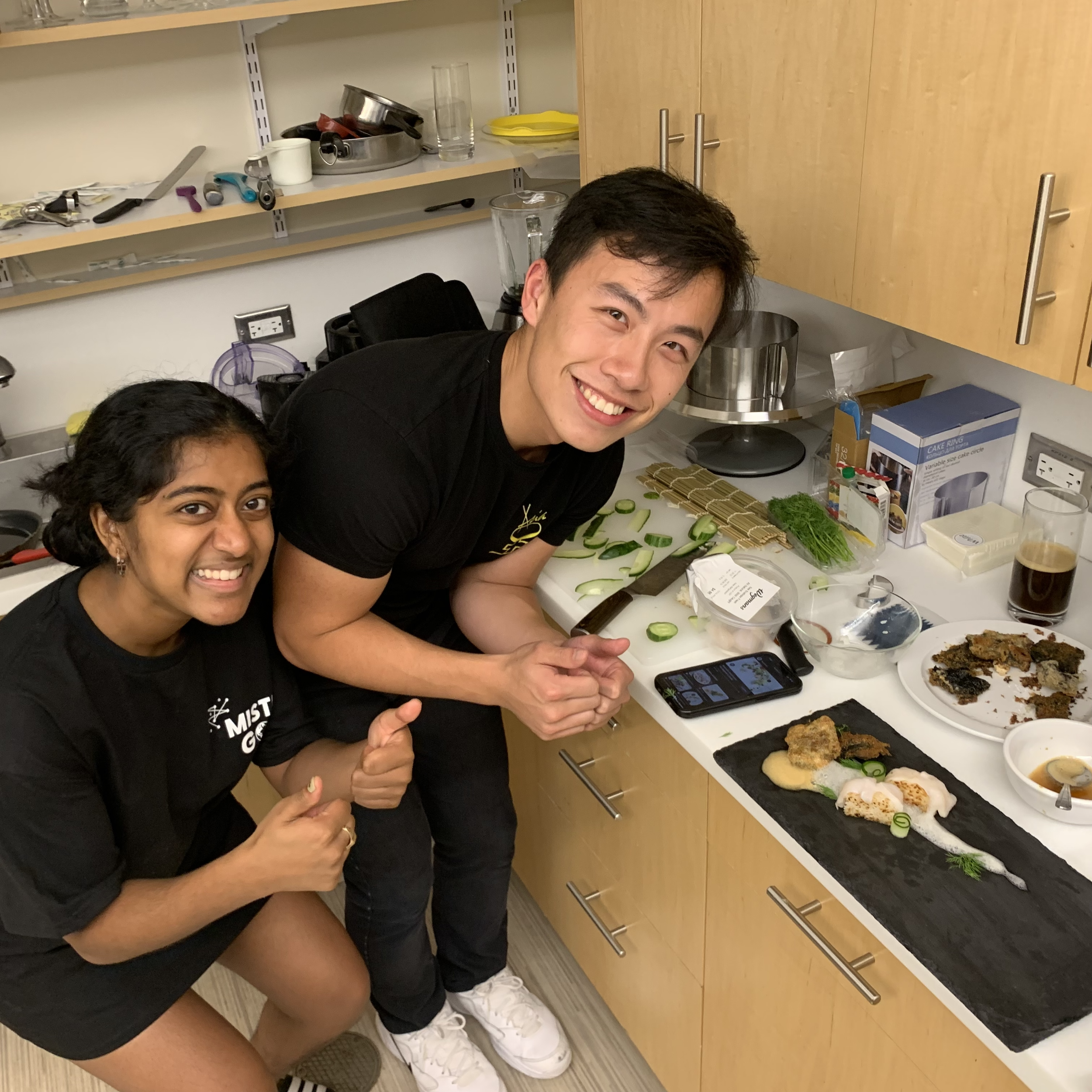

Michael Chen, Sangita Vasikaran

Perhaps we strayed a bit from our classical inspiration for this dish, bathing the scallop in fire instead of delivering Venus from the sea. For that matter, we also couldn’t find appropriately-sized seashells. Despite these compromises, Sangita and Michael on the starter team completely nailed the modernist aspect of this dish, featuring crispy sushi rice inspired by Chef Jean-Georges Vongerichten; fried nori chips; cucumbers; and most importantly two types of foam reminiscent of the white crests on ocean waves. Making airy foams out of soy lecithin was a technique that none of us had attempted before (which, as you’ll later see, seems to be a recurring theme.) Beyond emulating sea foam, this technique allowed the sauces – a traditional wasabi soy sauce and a tangy lemon sauce – to be presented with a deceptive lightness that complemented the fried and torched elements.

Main – “Compositions” Mondrian’s duck breast three ways

Jacky Cheng, Sophia Wang, Anika Cheerla

While the starter began with a largely traditional form – sushi – and added some modern twists, the main course was the exact opposite. For the heartiest dish on the menu, we set out with a modern form in mind and tried to recapitulate traditional dishes in a novel framework.

The theme: cubes. Or squares. Or straight lines. Or just anything that we could plausibly connect to Mondrian’s paintings, really. The composition (no pun intended) of the dish was altered several times throughout the R&D process, such as when cleanly-trimmed cubes of duck breast were abandoned in favor of more traditional slices, or when duck fat potato puree sandwiches were added into the dish last-minute as filling accompaniments.

The core elements of the dish, thankfully, remained the same throughout the R&D process. Duck breast, dry-aged for seven days, seared, and briefly cooked sous vide, was paired with reimagined versions of three traditional duck dishes: canard à l’orange, duck with scallion, and duck pastrami. In our rendition, the orange sauce was reimagined in the form of a safflower-orange jelly; the scallion was transformed into an aspic made of duck broth and scallion; and the pastrami was presented as crisscrossing lines of dry spices.

One crucial, contemporary element of the dish that MINCE attempted for the first time was the sous vide technique used to cook the duck breast. Sous vide, meaning “under vacuum” in French, refers to using a temperature-controlled water bath to precisely control the cooking process. In this case, the technique was used to bring a tender cut of meat to a perfect medium-rare throughout. More importantly for this pop-up, sous vide allowed us to cook on site in the MINCE portable kitchen – as long as we had access to electricity, we could cook. In the words of Thomas Keller in his sous vide cooking Bible Under Pressure: “sous vide is liberating.”

Dessert – “Waterlilies” Monet’s white chocolate matcha genoise

Monserrate Navarro, Alayo Oloko, April Wu

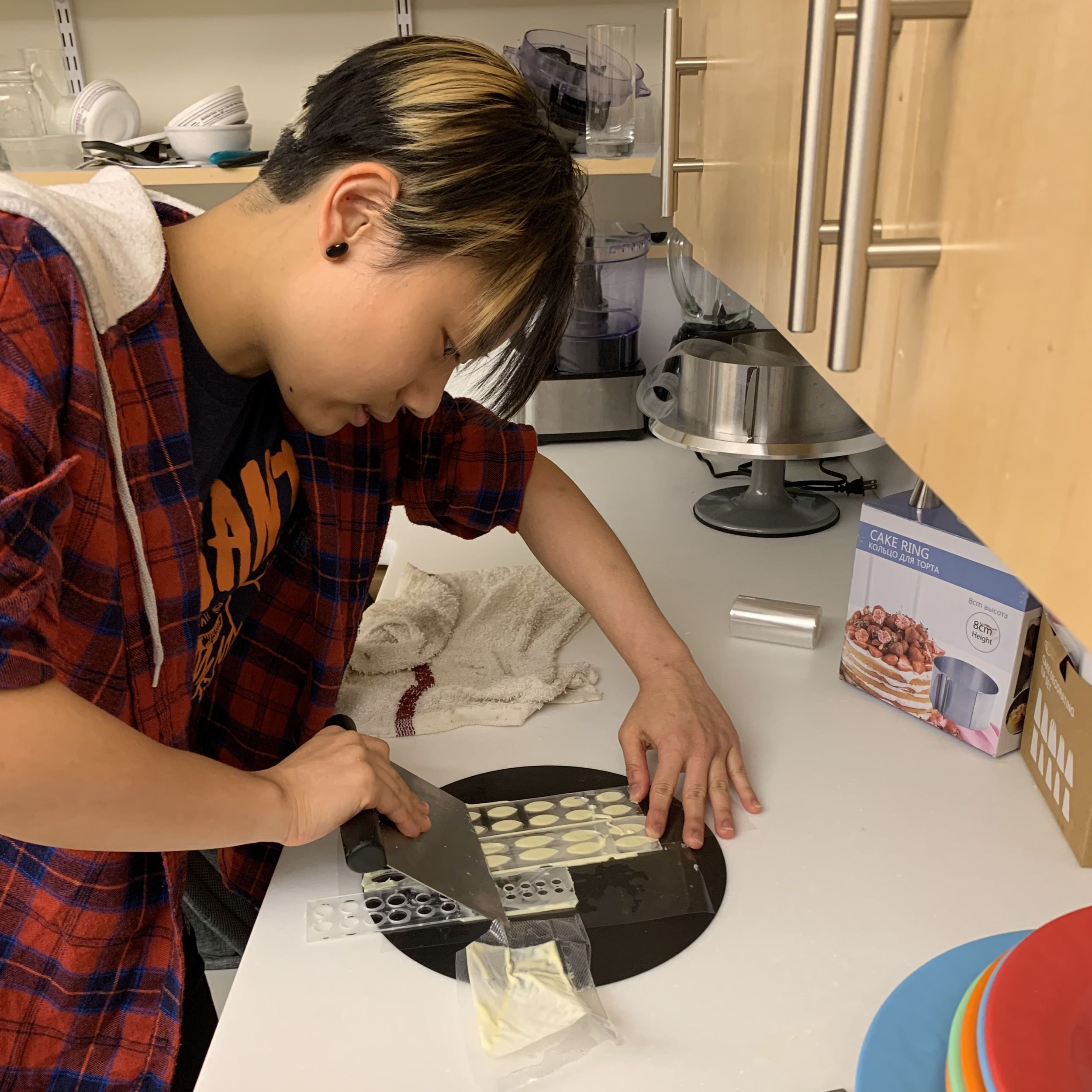

While the starter incorporated culinary foams and the main course featured sous vide cooking, dessert team took the modernist in modernist cuisine to another level. Like almost every other element in this pop-up, this too came after loads of trial and error. The original concept was simple, if not naïve: to make a matcha cake reminiscent of a lily pad, and adorn it with a lily flower made out of white chocolate. Someone on dessert team even told me, with full confidence, that we could probably make enough petals for each guest to receive their very own chocolate flower. “We’re just piping chocolate,” we thought.

We were wrong. Three days before the pop-up, we discovered that nobody on the team knew how to temper white chocolate. Our dreams of pumping out massive numbers of handmade chocolate petals on acetate paper were broken, in stark contrast with the soft mess of untempered chocolate that refused to snap cleanly like we wanted. Thankfully, we had Monse, a mechanical engineer by training, who quickly figured out the most MIT-esque alternative possible: instead of forming the chocolate by hand and hoping for it to temper, we could mold the chocolate in a piece of CAD/CAM laser-cut acrylic, then chill it so that the chocolate, albeit not tempered, could still solidify into our desired shape. Then, we could assemble the flowers by cementing two layers of petals onto a circular base with molten chocolate. The cold Boston winter finally put itself to some good use, too, temporarily transforming our kitchen to a cold room where piped chocolate cement hardened in seconds.

The rest of the dessert went smoothly. April perfected the recipe for moist, flavorful chocolate genoise, and Alayo whipped up a cream that filled the palate with an exquisite rosewater aroma. After assembling four cakes for the guests, they even found a great use for the leftover materials – with irregular pieces of genoise trimmings, April assembled a cake for MINCE members. Then, using her oil painting skills, she decorated it with a Monet-esque vista that arguably was more evocative of water lilies than our official dessert. What a great time to be in MINCE!

Drink – “Starry Night” Van Gogh’s 4D butterfly pea drink

Feli Xiao, Tananya Prankprakma

We made the decision to serve the drink last, after the dessert, as opposed to during the meal, in order to highlight this unique beverage that deserved to be appreciated with full, undivided attention. Inspired by the concept of “multisensory experience” – a culinary movement where of the diners’ senses are stimulated in a carefully curated experience that ranges beyond the food itself, we came up with the idea of a “4D” drink without really knowing what the four dimensions represent.

Starting with the idea of having a butterfly pea flower drink that visually changes color when acidic yuzu juice was added (1/4), we decided to not only incorporate music (2/4), but also add a special scent using essential oils (3/4), an idea that was made possible thanks to Sophia’s roommate Selena, our special consultant for all things essential oil-related.

Wait a minute, you might think. Where’s the fourth dimension? Well, it turns out that we couldn’t settle on proper taste profile for the tea. On its own, the taste of butterfly pea flower was reminiscent of corn, and even though both members of drink team hailed from the Midwest, we were hesitant to serve a corn-flavored tea. Feli brought dried rose buds from home in an attempt to rectify the taste, but the roses’ delicate flavor was not strong enough to overpower the smell of corn. In the end, we found that by starting with jasmine tea and briefly blanching the butterfly pea flowers, we could have a flavor base that our diners were familiar with, upon which we could build the other dimensions of this multisensory experience.

Another important element in this dish was the incorporation of gold foil. Back in the menu ideation session, I pitched the idea of using special (read: luxury) ingredients commonly associated with fine dining, trying to convince the powers-that- be that when purchased at scale, truffles and caviar aren’t really that expensive. Obviously, I failed. Thankfully, however, the concept took off. We ended up incorporating gold flakes in the drink – specks of shining light that swirled around the glass as the drink was being poured, just like the swarms of stars in “Starry Night.”

Decor and service

Remember, back when we first set out on this journey, how Angela asked me what vision I had for this pop-up? It turned out that she was thinking about decor long before menu ideation began – even after almost a whole semester with MINCE, I was again struck by how much behind-the-scenes work went into putting a pop-up together, reaching far beyond just cooking in the kitchen, from the dedication of the decor team to the professionalism of our servers.

Fortunately for Angela, my vision of “modernist cuisine” wasn’t difficult to pair with when it came to decor. Going by the name alone, we could choose a theme of modern art, or, we could focus on the contemporary nature of our food and march into postmodernism. Angela chose a mix of both: inspired by a range of artwork, from “The Son of Man” to “Balloon Dog” to “Banana Taped to Wall,” she combined the artists’ influences and added her own touch to create a unique set of decorations that ranged from subtle to outright playful. My favorite was the menu – a Jeff Koons-style rendition of “The Son of Man” that was subtly strung together with the apple and balloon animal decorations in the dining room.

What’s more, the decorations served a practical purpose in addition to an aesthetic one. For the “smell” dimension in the drink, we experimented with many different ways of delivering the essential oil: adding it directly to the drink, filling balloons with it, or even rubbing it on the servers’ wrists. In the end, we decided to infuse the oil into reed diffuser sticks, and insert the diffusers into the balloon dogs’ “hands” right before the drink was served.

The end of the night

MINCE afterparties are the best, always filled with great food and drink and people. This time, we indulged ourselves with extra dessert and drink (I recall with great pride that scraps from the main dish were gone long before the meal ended.) And, as always, there was great conversation, as we all unwound after a long evening of service.

At the end of the day, did my food connect with the guests? Was MINCE successful in communicating the “wow factor”, that sense of excitement and discovery that comes to us when we discover good food? Did we convince anyone that food is more than merely bodily sustenance, than paying for calories and nutrients, but rather nourishment for our hearts and souls? I do not know.

Perhaps it is futile to ponder such questions. After all, “if you gaze long into an abyss, the abyss also gazes into you.” What I do know, however, is that my fellow MINCE members and myself had an absolutely wonderful time. Perhaps this is enough, to know that there are people in this world who share the same vision with myself; and to know that I am fortunate enough to get to meet these people and realize this vision with them. Perhaps this is part of the “nourishment” that my favorite chefs have been talking about – that during the process of cooking, we as chefs have nourished not just our guests, but also ourselves.